ANSO, RAT BEDLINGTON, LEO COYTE, IAN HAIG, ANGUS MCGRATH, AUDREY NEWTON & YVETTE JAMES

’HORROR IS NOTHING OTHER THAN REALITY’

6 JULY – 4 AUGUST, 2023

OPENING NIGHT: 6 JULY

Leo Coyte, Gone, 2023, oil and acrylic on canvas, 137 x 112 cm . Image courtesy of the artist.

ID: This is a close up of an abstract painting. It has various abstract shapes overlapping each other, each coloured with different layers of yellow, orange, red and green across the page. In the middle there is a large black dot with another black semi-circle beneath it. To the left of the semi-circle, there is a garden gnome laying on its stomach, with a blue hat, shirt and pants. The gnome has a grey beard and its eyes shut, with its pants lowered, exposing his behind.

CURATORIAL STATEMENT

Horror Is Nothing Other Than Reality exposes the alienating and gnarly nature of species entanglement, through a set of mutable assemblages composed of hardware and organics. Horror Is Nothing Other Than Reality preys on our fears, falling into post-apocalyptic and futuristic tropes. Yet, stepping back, we see a familiarity in the works and understand that they are quite close to our current reality.

Horror Is Nothing Other Than Reality is chapter one in a series of exhibitions that look critically at human-centric states of play. The second chapter, Entangled Me, occurs in November 2023.

CW: Supernatural themes and strong graphic imagery.

Horror is Nothing Other than Reality, 2023, Installation view. Photography by Jessica Maurer.

ID: In Verge Gallery from the left, there are latex pillows that scatter the bottom half of a pink wall. They are all various sizes and textures, but all have a brown-yellowish tinge to it’s colouring. This same latex drips from the top of the pink wall and down to the pillows. In the far back of the gallery, there are three brightly coloured paintings that then end with a screen. In the right forefront, is an abstract colourful painting with three black dots descending down it.

A glimpse into the world proves that horror is nothing other than reality.

- Alfred Hitchcock

Horror is Nothing Other Than Reality applies the same methodology that characterises Hitchcock films, that is, engaging with tensions which arise as a natural result of our everyday experience within contemporary society. The exhibition acts as a multi-species landscape which responds to and questions technophilic ideologies and hierarchies created via the nature/culture divide. The ‘horror’ in Horror is Nothing Other Than Reality flows from an exploration of an external, often incomprehensible, force permeating one’s personal sphere of being. At its core, Horror is Nothing Other Than Reality exposes the alienating and gnarly nature of species entanglement—whether that be in relation to the enmeshment of humanity and technology or in respect to a violation of human boundaries by other-wordly, supernatural beings. Through mutable assemblages composed of hardware and organics, Horror is Nothing Other Than Reality preys on fears that at first glance fall into post-apocalyptic and futuristic tropes, however, stepping back, are seen to be familiar, compelling us to recognise that these horrors, once thought as distant, are in fact current realities.

Horror is Nothing Other than Reality, 2023, Installation view. Photography by Jessica Maurer.

ID: In the forefront is Yvette James’ creature, it is a steel structure with four slim legs and a plastic white sheet draped over top of it. Behind it is Ian Haig’s video work, sitting on a screen the work depicts human like faces with bits of technology surgically placed into it. On the far left there is Leo Coyte’s brightly coloured abstract painting and in front with Audrey Newton’s yellow brown textile blobs sitting on the floor. On the far right there is Yvette’s artwork which is a steel panel that his brightly lit.

Illustrating the violation of privacy across biological and technical boundaries are works by Yvette James, Audrey Newton, and AnSo, who, through abstracted imagery, comment on the vulnerability of humanness. James' Resting Under the Encrypted Veil (2023) is a spindly alloy figure, representative of the weak human form, on which is draped a white ‘opaque screen.’ This work attempts to expose the actuality that humans are manipulated and categorised by the data systems which they create. The two-symbol digits etched into James’ Information Overwhelm (2023) extends upon this notion further, critiquing the way in which technology delineates the fluid intricacies of humanity into marketable binaries.

Audrey Newton, The Skin That Speaks (i think you're brilliant. I don't think I've ever told you that, but it's true.), 2023, latex, beads, fabric, jelly wax, hobby fill, doll hair, dirt, dimensions variable. Audrey Newton, The Skin That Speaks (i think you're brilliant. I don't think I've ever told you that, but it's true.), Installation view. Photography by Jessica Maurer.

ID: On the floor there are two piles of skin-like textured pillows, orange-pink coloured, they are all different sizes covered in latex with a shiny coat on the outside. They have a pink wall behind it with dried latex dripping down the wall.

Approaching human vulnerability through a biological lens, Newton’s bulbous, fleshy lumps entitled The Skin That Speaks (i think you're brilliant. I don't think I've ever told you that, but it's true.) (2023) explores dermis as a communicator of our internal world with its permeable and reactionary nature, allowing for the invasion of bacteria and a divulgence of our inner feelings. Aligning with these ideas of vulnerability, AnSo’s sonic work creates an immersive realm in which viewers are encouraged to become introspective, allowing audiences to be hyper-aware of their vulnerabilities as they move throughout the exhibition.

Ian Haig, Useless Eaters, 2022, single channel video, 48m looped, edition 1 of 10, Installation view. Photography by Jessica Maurer.

ID: There’s a screen in the middle of a white wall with Ian Haig’s work on it. His work depicts a human-like face with bits of technological materials surgically placed in it, this is an AI generated image.

Ian Haig’s Useless Eaters (2022) and Leo Coyte’s Gone (2023) and Dross (2023) introduce a series of ironic and eccentric odd fellows created randomly and/or by chance — Coyte employing methods of free association to subconsciously call upon images from the depths of his mind and Haig utilising AI as a tool to generate modified organs. The characters in Haig and Coyte’s works are at once horrific, awkward and exposing, with both interrogating what it is to be human today. However, where Coyte mines the subliminal, Haig confuses the biological. Coyte’s fragmented painterly symbols play on the familiar, drawing upon traditional, well-known semiotic language, evoking a sense of fear not through the introduction of new horrors but by recalling symbols, such as hell fire and witches, that the viewer knows to be horrific. Touching on the transhumanist, extropian musings of ‘cult’ theorist Yuval Noah Harari, Haig’s more-than-human hybrids are jarring for exactly the opposite reason: they expose unfamiliar, seemingly unnatural ‘dis-arrangements’ of flesh and hardware. Here, Haig considers these monstrous distortions and hacked body parts to illustrate the prospect of our future consciousness being downloaded from the cloud.

Leo Coyte, Gone, 2023, oil and acrylic on canvas, 137 x 112 cm . Installation view. Photography by Jessica Maurer.

ID: Leo’s painting is hung on a white wall. It has various abstract shapes overlapping each other, each coloured with different layers of yellow, orange, red and green across the page. In the middle there is a large black dot with another black semi-circle beneath it. To the left of the semi-circle, there is a garden gnome laying on its stomach, with a blue hat, shirt and pants. The gnome has a grey beard and its eyes shut, with its pants lowered, exposing his behind. To the left of the painting there is a faint image of a person walking into the frame, wearing all black.

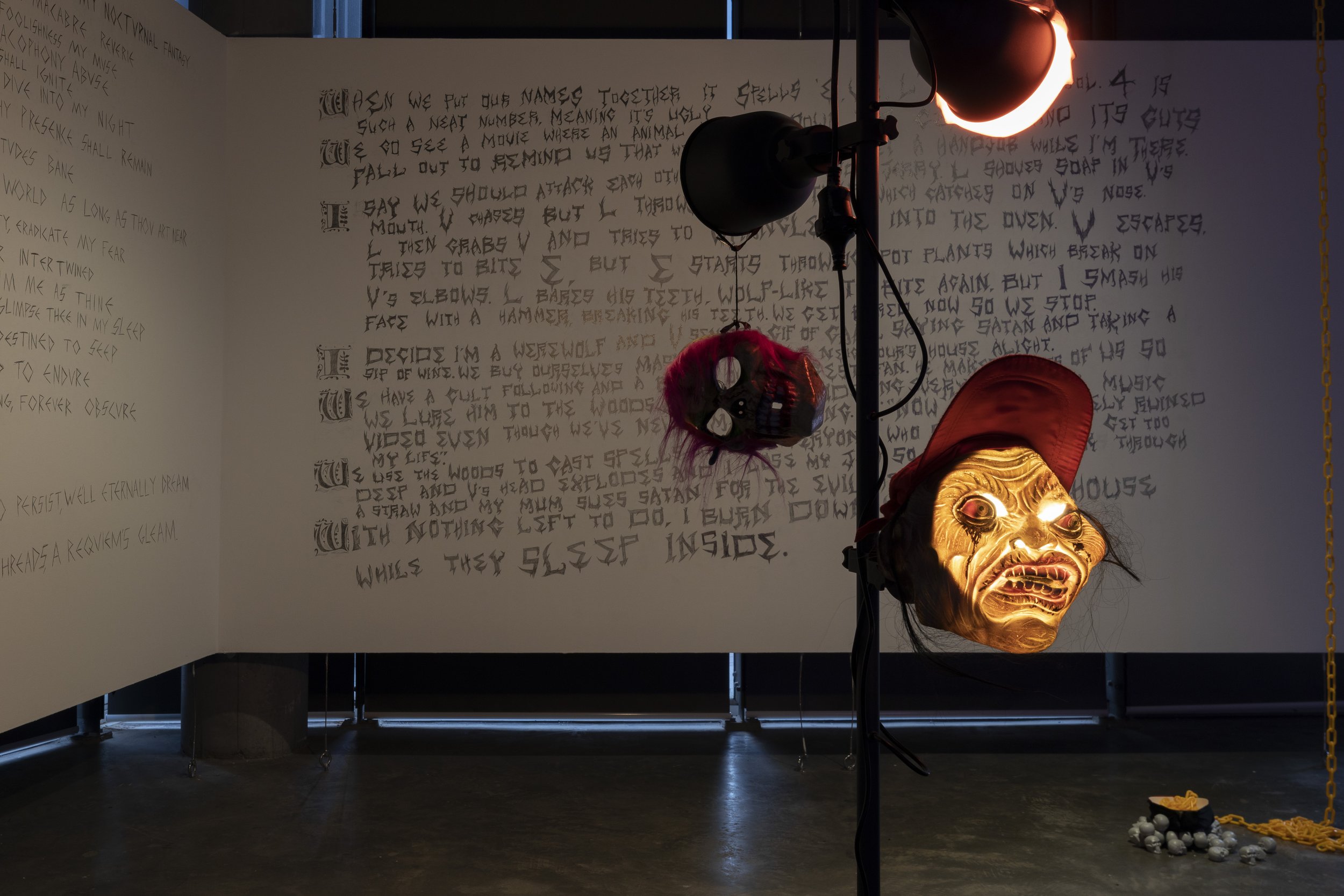

Both Rat Bedlington and Angus McGrath comment upon the often-avoided dark, poisonous aspects of human nature. McGrath’s installation Constant Nothing (2023) approaches this horrific reality through the lens of ‘teenage-ness.’ McGrath examines the fact that when adolescents commit unspeakable acts, an easily-sourced excuse is proffered as a substitute for the more uncomfortable possibility that the motivation for committing such acts might be outside of our realm of understanding. McGrath communicates that there are multitudes that are unknowable about real life horror, and humanity might have a greater propensity for darkness than we have traditionally, collectively liked to think.

Angus McGrath, Constant Nothing, 2023, installation of text on wall in pencil, eraser, dimensions variable, installation view. Photography by Jessica Maurer.

ID: In the forefront, there is a light stand with halloween masks hung on each light to make their faces glow a orange-yellow colour. In the back, the white wall is covered in penciled text explaining a story from the artist. On the floor next to it, there is a yellow chain that is hung from the ceiling to the floor with the chain going into another halloween mask face, as it lies on a pile of grey miniature skull heads.

Relatedly, Bedlington’s series of works looks at the propensity for humans to act in horrific ways; however, unlike McGrath, Bedlington considers this ‘reality’ from the perspective of other-worldly, supernatural beings. Demons, presented in Bedlington’s video work Demoni-logue (2023), share their thoughts on the ‘perplexing, hubristic activity of human beings.’ These artists' works not only support but build upon Hitchcock’s famous assertion that horror is nothing other than reality, suggesting that the horrors that we experience in this world are potentially born out of an unexplainable dark streak existing within the human psyche.

Rat Bedlington, Horror is Nothing Other than Reality installation view, 2023.

ID: On the white wall, there are five paintings and a screen in the middle. On the left there are three various sized paintings, the first being a keyhole with a person’s eye peeping through. The next a bottom portion of a face grasping and kissing another person’s body part. Third a larger painting having two floating heads in red water with a red sky, in the sky there is a circle with another person looking down at the two heads.

In the middle, there is a screen depicting sequins across it, with two headphones dangling below it. On the right hand side, there is another painting of a keyhole with someone getting dressed inside of it. With the last work being a large canvas, bordered in plush blue cushion, with a person laying on green grass with a dark creature laying over them.

Horror is Nothing Other Than Reality is a reflection of the tensions that we experience as humans living in a contemporary capitalist world. While the tone of the exhibition is by and large tongue in cheek, some works may be confronting to members of the community. We encourage audiences to approach the curatorial staff who are on hand to speak about the nature and intention of the works. Horror is Nothing Other Than Reality is chapter one in a series of exhibitions that consider the construction of species intelligence and identity, looking critically at human-centric states of play. The series highlights our current existential crises and refutes the notion that human identity is separate from other intelligences, beings, and machines. The second chapter, Entangled Me, will look at the sensual and spiritual nature of species entanglement and will occur in November 2023.

Tesha Malott & Anthia Balis

Horror is Nothing Other than Reality, 2023, Installation view. Photography by Jessica Maurer.

ID: In Verge gallery, Gus, Rat and Audrey’s work are visible from this angle. With the lamp with halloween masks in the forefront, and Rat’s paintings across the wall on the right. In the far back middle, Audrey’s pillows sit on the floor with vibrant lights hitting them.